Whatever became of the

Brennan Typewriter

But ROBERT MESSENGER has happily unearthed an Australian typewriter inventor … of sorts

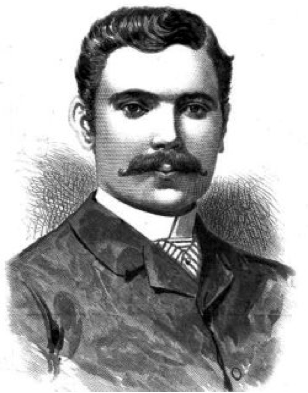

WHEN, in June 1889, Louis Brennan, the Australian mechanical engineer who invented the world’s first guided missile, was told the great American naval commander Winfield Scott Schley had come up with a torpedo which would “forthwith render his obsolete”, Brennan was utterly unfazed. He had heard these sorts of stories before, Brennan gruffly retorted, “on the average once a month, and always on the best authority”. And, he went on to stress, “somehow the new torpedo itself never puts in an appearance”. (In the case of the Schley missile, at least, it seems Brennan was right.)

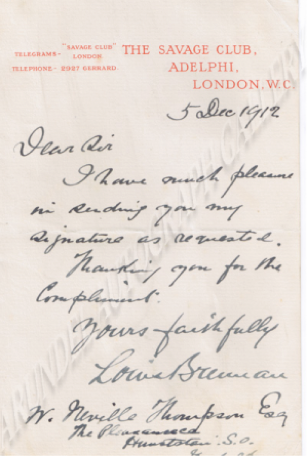

Brennan informed his close friend and fellow Savage Club of London member, the journalist and politician John Henniker Heaton (left), he had more pressing matters on his mind. He had found time away from developing his dirigible torpedo – for which the British Government had paid him a sizeable fortune - to return to one of his earlier, major ambitions: to design and build a portable typewriter.

The portable typewriter was an idea Brennan had been working on since he was still at technical college in Melbourne, in 1873. While concentrating on his torpedo, however, he had been frustrated to learn that events in the United States with regard to a writing machine had overtaken him: not alone had a practical typewriter (right) been invented, but it had gone into production at E.Remington and Sons at Ilion in New York and was being sold in various parts of the English-speaking world.

Indeed, Brennan had even worked on a Sholes and Glidden typewriter. In late 1876, he repaired one for his then employer, Alexander Kennedy Smith, one of the first men to import a typewriter into Australia.

Kennedy Smith and Brennan were both inclined to describe the Sholes and Glidden as a “printing machine” as well as a “type-writer”. Even before being apprenticed to Kennedy Smith, Brennan had started working on a wide range of contraptions, some in collaboration with an English-born printer, William Samuel Calvert. Calvert was also an engraver and etcher who described himself variously as an “electrotypist”, “ornamental printer” and lithographer. Brennan and Calvert became associated two years after Brennan had enrolled as a technical student at Joel Eade’s Collingwood School of Design and its auxiliary, the Artisans' School of Works, for “rising operatives”, in 1871. Brennan showed some of his earliest efforts at a “juvenile” industrial exhibition in 1873 and at about this same time he confided his interest in inventing a writing machine to Calvert.

In has to be emphasised that during this period of the early 1870s, Brennan, based in a country far distant in terms of travel from and communications with Europe and America, might sometimes have been thinking of machines which, in a few cases, had already been built, but the existence of which he was completely unaware. Another biographer, Richard Ross, wrote in Walkabout magazine in June 1969 that Brennan “may seem to have been an emulator, but if so he was an unwitting one”. Tomlinson adds that “it was possible that some ideas original to Brennan, and original in the Australia of the 1860s and 1870s, may well have appeared already in similar form elsewhere, although this would not minimise Brennan’s own imaginative and practical abilities.”

In late 1876, however, Brennan became fully aware of what Christopher Latham Sholes and his colleagues had managed to get Remington and Sons to make, when he was asked by Alex Kennedy Smith to repair Kennedy Smith’s Sholes and Glidden. At this point, it seems, Brennan put aside his typewriter idea for the time being to concentrate on his torpedo and a multitude of other inventions. He was not to pick up his portable typewriter plans again until the middle of 1889, 13 years later. By that time, the Remington typewriter had been joined in the market place by other brands and styles. But a designated portable typewriter was still some years away – four, if one includes the Blickensderfer 5, or almost 20 years if one insists on the Standard Folding as the first portable.

In an interview published in The Adelaide Advertiser in 1907, Brennan outlined the discovery which led to his dirigible torpedo. It happened while he was working in Kennedy Smith's workshops. “I stumbled upon a novel mechanical paradox, namely, that it is possible to make a machine travel forward by pulling it backward.” Brennan went on to say that “Accident is the mother of invention in 99 cases out of 100. A new principle is stumbled upon, as in this instance, and presently comes the idea of applying it to some certain thing for which it would seem to be eminently and specially suitable.”

It could well be speculated that when Brennan took apart Kennedy Smith’s Sholes and Glidden to repair it, he saw possibilities for improving the typewriter and making it much more compact - just as he had envisaged a torpedo while working with Kennedy Smith’s planing machine.

Certainly, Brennan’s close ally, the journalist John (later Sir John) Henniker Heaton, had sufficient faith in Brennan’s abilities to express in print his belief that the Australian inventor could improve on the Remington if not all other existing typewriter models.

He was a staunch Australian nationalist who through Brennan took every chance to promote Australian innovation. Heaton also pushed into existence penny-stamp mail beweetn England and Australia and penny-a-word telegrams. He represented Tasmania at the 1885 International Telegraphic Conference in Berlin and gave evidence to the 1887 Colonial Conference in London. He won deductions in cable rates, brought international telegrams within the reach of the ordinary man and enabled Australian newspapers to give a fuller coverage of world news. Heaton was a fellow of the Royal Colonial Institute and the Royal Society of Literature.

There were certainly enormously high hopes for the Brennan typewriter. In early July 1889, colonial newspapers published glowing predictions contained in a Press Association dispatch from London. “Louis Brennan, whose torpedo has brought such honour to Australia, is now busy perfecting his new type-writer in London. There can be no doubt that if the machine fulfils the young Antipodean’s expectations, it will entirely supersede the Remington, the Hammond (left), and the Bar Lock [sic], which have so far alone been found to be wanting in practicality.

These forecasts proved to be, of course, grossly exaggerated. There is not even evidence Brennan did patent a typewriter, at least not in 1889. Many of Brennan’s earliest, Australian inventions certainly were never patented. But there are records of 38 patented Brennan inventions, ranging from his torpedo (right) to a helicopter, his monorail, a gyro-car and a lift for stairs.

Louis Philip Brennan was born on January 28, 1852, on Main Street, Castlebar, County Mayo in Ireland, the son of a hardware merchant. One of his older brothers, Patrick, migrated to Australia in 1856 and taught in Melbourne. Another, Michael, worked as a journalist with the Connaught Telegraph and later became a noted artist.

By the time Brennan’s parents decided to join their eldest son in Melbourne, in 1861, the nine-year-old Louis had already developed a keen interest in difficult puzzles and mechanical toys. On the long sea voyage out to Australia, the workings of a shipment of clocks had become seized by salt air, and to the delight of the importer, Louis was able to get them ticking again.

Brennan developed his monorail at his home and in 1910 it won the highest award at the Japan-British Exhibition in London. In 1919-26 he worked at the Royal Aircraft Establishment, Farnborough, on the development of his helicopter, but it crashed on a trial run in October 1925. He was elected an honorary member of the Royal Engineers Institute in 1906 and a foundation member of the National Academy of Ireland in 1922.

While on a recuperative holiday in Montreux, Switzerland, Brennan was knocked down by a car on Boxing Day 1931 and died three weeks later. He was buried in London.

So what ever became of the great man’s typewriter? If this was to be a Brennan-designed machine which would so comfortably outstrip Remington, Hammond and Bar-Lock, how could it have possibly failed?

Brennan did return to his portable typewriter one more time – in July 1922, almost half a century after the idea had first come to him, as a 21-year-old technical college student in Melbourne. By the early 1920s, Brennan had exhausted efforts to get the British and Australian governments or the India Office to put substantial sums of money into his monorail. His added problem was that, by that time, the typewriter had been developed almost to its ultimate stage. Corona (from 1912), Underwood (from 1919) and Remington (from 1921) had come to dominate the portable typewriter market with small, lightweight machines which were engineering gems.

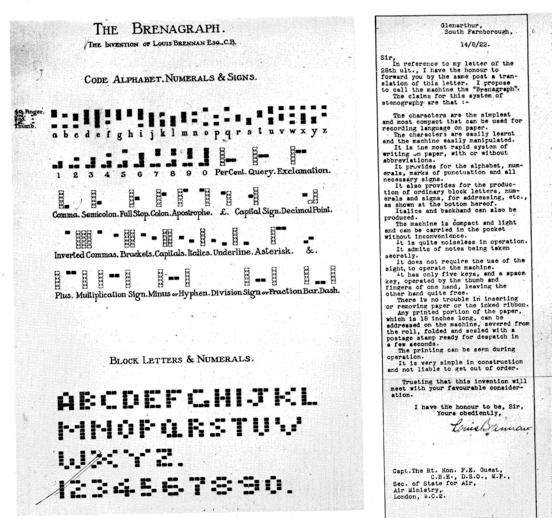

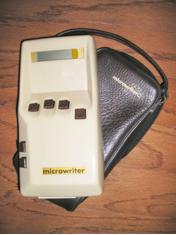

Brennan needed to rethink his original ideas – and he came up with the “Brenagraph”. It was more a stenotype than a typewriter.

Tomlinson wrote, “So many of Brennan’s ideas have reappeared in practical form, that it is particularly interesting to mention his ‘Brenagraph’ … He worked on the basic ideas simultaneously with breaks in the work on the helicopter, and eventually produced a pocket-sized machine 5in x 4in x 1in (10cm long, 8cm wide, 2cm high). It had five keys which were pressed, rather than struck like a conventional typewriter, and was completely silent. One key also operated in a sideways movement for spacing and there were similar ingenious arrangements signally the approach of the end of a line and for a line shift.

“The five symbols were used in various combinations, not unlike the Morse code, to represent all the letters of the alphabet, the 10 numerals, and various punctuation signs. Just as war-time conscription showed how easily the average man could learn and operate Morse at speed, so Brennan’s code would require little practise before it could be similarly used. Indeed, for brief note-taking, it would have been quite reasonable to dispense with punctuation, and even spacing.

“A roll of paper was used in conjunction with an inked ribbon. Brennan’s always busy mind also conceived the idea of using a power-driven perforated roll which would cause the keys to pulsate in order to help a blind person to read without the slow and laborious process of finger-scanning Braille type.

“At the time, always mindful of possible governmental and services needs, Brennan offered the idea to the Air Ministry for the use of pilots for taking notes during darkness. The offer was not taken up because the Ministry could conceive of no use for the Brenagraph.”

And thus ended the history of the Brennan typewriter, the great portable typewriter that never was. For all his wonderful ideas, Brennan is very much today a forgotten man – his torpedo was indeed superseded, his monorail was never fully utilitised, and his helicopter was never completed. Maybe a Brennan typewriter, if it had ever been built, might have made a difference. On the 50th anniversary of his death, in 1982, Melbourne’s The Age quoted the Victorian State historian, Dr Bernard Barrett, as saying Brennan was “an early example of Australia’s brain drain”. “Australians are accustomed to their technology being imported,” the newspaper said. “We tend to forget some creative minds have been at work in this country.” And that includes a mind that was once put to coming up with an Australian typewriter.